-

- Author, Sarah Rainsford

- Author's title, Correspondent of El Sur and East of Europe, BBC

When you go down the winding and narrow main street of its town in northern Italy, Giacomo de Luca points out the businesses that have closed: two supermarkets, a hairdresser, restaurants, all with the closed countervanas and notices faded above its doors.

The beautiful town of Fregona, at the foot of the mountains, is emptying the same as many others here, as the Italians have fewer children and increasingly emigrate to larger locations or move abroad.

Currently, local elementary school is at risk and the mayor is worried.

“The new first year can't continue because there are only four children. They want to close it,” says De Luca. To receive financing, the minimum class size is 10 children.

“The fall in birth and population has been very, very acute.”

The mayor estimates that the population of Fregona, one hour by car north of Venice, has shrunk in almost a fifth in the last decade.

Enter June of this year, there were four new births and most of the almost 2,700 residents who remain are older people, from men who drink a morning of Prosecco to women who fill their chicory bags and tomatoes in the weekly market.

For De Luca, the closing of the first year class could be a crucial moment: if the children leave Fregona to study elsewhere, fear that they never look back again.

So he has been traveling through the surrounding region, and even visited a neighboring pizzas factory, trying to persuade parents to send their children to their people and help keep the school open.

“I am offering them to collect them in a minibus, we have offered that the children remain in school until six in the afternoon, all paid by the City Council,” the mayor told the BBC with an obvious sense of urgency.

“I am worried. Little by little, if things continue like this, the people will die.”

A national problem

The demographic crisis of Italy goes much further than scrubon and is being deepened.

In the last decade, the national population has contracted in almost 1.9 million people and the number of births has fallen for 16 consecutive years.

On average, Italian women are having only 1.18 babies, the least registered level. That is below the EU fertility level of 1.38 and well below the 2.1 necessary to maintain the population level.

Despite the efforts to foster birth and a lot of rhetoric for pro family policies, the right -wing government of Giorgia Meloni has been unable to stop the descent.

“One has to think long before having a baby,” says Valentina Dottor when we are in the Central Plaza de Fregona, lulling her 10 -month daughter daughter in a stroller.

Valentina receives a subsidy of about € 200 (US $ 232) per month during the first year of life in Diletta, but was excluded from the new government baby bonus of € 1,000 (US $ 1,160) for children born in 2025.

There are also tax credits and more maternity leave.

But Valentina now needs to return to work and says it is still difficult to have access to child care at moderate prices.

“There are not many babies, but not many places in the nurseries,” he says. “I'm lucky to have my grandmother to take care of my daughter. If not, I don't know where I would leave her.”

That is why her friends are suspicious of being mothers.

“It's difficult, for work, schools, money,” adds Valentina. “There is a bit of help, but it's not enough to have babies.”

“It won't solve the problem.”

Self -help programs

Some companies in the Veneto region have taken letters in the matter.

At a short distance to the Valley from Fregona there is a large industrial complex full of small and medium -sized companies, many administered by families.

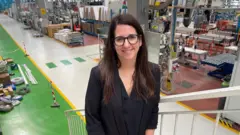

Irinox, an ultra -grared freezer manufacturer, realized the problem of raising children a long time ago and decided to take action before losing valuable employees.

The firm united forces with seven others to create a nursery a few steps from the factory, which is not free, but it offers a great discount. It was the first of its kind in Italy.

“Knowing that I could leave my son two minutes from here it was very important, because he could reach him at any time, very fast,” explains Melania Sandrin, one of the firm's chiefs of finance.

Without the nursery, I would have difficult to work again: I did not want to put a burden on their parents and the nurseries of the State generally do not take children for a full day.

“They also have a priority list … and there are very few places,” says Melania.

Like Valentina, she and her friends took the thirties to have children, interested in establishing their careers, and Melania is not sure that she wants a second baby. “It's not easy,” he says.

Late birth, a growing trend here is another factor that lowers fertility rate.

For all that, the executive director Katia da Ros thinks that Italy needs to adopt “huge changes” to address her population problem.

“It is not the payments of € 1,000 that make a difference, but there are services such as free nurseries. If we want to change the situation, we need firm action,” he argues.

The other solution is an increase in immigration, which is a much more contentious issue for the Meloni government.

More than 40% of employees in Irinox are foreigners.

A map on the factory wall shows with studs that come from Mongolia to Burkina Faso. Unless there is sudden boom in birth, Katia da Ross argues that both Italy and the Veneto will need more foreign workers to boost their economies.

The end of a school

Immigration could not save a school in the neighboring town of Treviso.

Last month, Pascoli Elementary School closed its doors forever because there were not enough students to hold it.

Only 27 children gathered in the staircases of the school for the final ceremony marked by a cornetist with a pen in his hat that touched the song “Last post” (used in British military funerals) as the flag of Italy was burning.

“It's a sad day,” said Eleanora Franceschi, picking up his 8 -year -old daughter for the last time. As of September, you will have to travel much further to go to a different school.

Eleanora does not believe that birth leave is the only guilty: he affirms that the Pascoli school did not teach in the afternoon, making life more difficult for working parents who then transferred their children to another part.

The rector has another explanation.

“This region has been transformed because many people from abroad came here,” Luana Scarfi told the BBC, referring to two decades of migration to the Veneto region for their multiple factories and numerous works.

“Some (families) then decided to go to other schools where the migrant index was not so high.”

“Over the years, we had less and less people who decided to come to this school,” says the rector, alluding to tensions.

A UN prognosis indicates that the population of Italy will fall into about five million in the next 25 years, of its current figure of 59 million. The aging of the population is also adding a burden to the economy.

Government measures to face this trend have achieved little.

But Eleanora argues that, to begin with, parents like her need more help with services and not just cash donations.

“We receive monthly checks but we also need practical support, such as free summer camps for children,” he says, calling attention to the three months of holiday from June that can be a nightmare for parents who work.

“The government wants a more numerous population, but at the same time it is not helping,” says Eleanora.

“How are we going to have more children with this situation?”

Produced Por Davide Ghiglione.

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.