Image source, AFP via Getty Images

-

- Author, Dia u preture

- Author's title, BBC News World

Many, many years ago (about 8 or 9 million), in that place that would later be called South America, when the Andes were in their adolescence, the vegetation was wild and the humans, non -existent, there were two plants …

“Rather, two plant populations,” he said, in an interview with BBC Mundo, Dr. Sandra Knapp, Taxonoma of plants at the Natural History Museum of London.

“They were the ancestors of what we recognize today as tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) and those of a group of plants called Solanum etuberouswhose three current species are in Chile and in the Juan Fernández Islands, “he added.

As perhaps you noticed by the names, they were relatives, and among them something happened even in the best families: they had sex.

The specialists call it interspecific hybridization and occurs frequently, sometimes with partial or totally unfortunate results.

The mule, for example, is born from an intimate encounter between a mare and an ass, and although it is a successful hybrid and appreciated since ancient times, it does not have the ability to reproduce.

In the plant kingdom, says Knapp, crosses between species “happen a lot: this is how we often get our garden plants.”

Naturally or with human intervention, “sometimes they hybridize and create a generation of plants that seem intermediate between their parents, but sometimes they are sterile, so they do not become a new population,” explained the expert.

But when the mixture of the ingredients is ideal, the fruit of the union exceeds expectations.

This was in this case: of that casual encounter millions of years ago between two species of the family Solanaceae The potato was born.

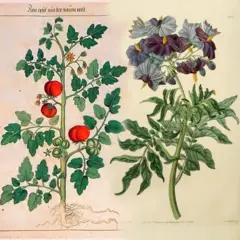

Image source, LOC/Biodiversity Heritage Library

“It is fascinating that something as everyday and as important for us as the potato has such an old and extraordinary origin,” said Knapp.

“We finally resolved the mystery of the origin of the potatoes,” Sanwen Huang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

“The tomato is the mother and the Etuberosum is the father,” added the scientist, who directed the international team that the developer studied in Cell magazine.

The origin was not the only unveiled mystery.

How they knew it

The starting point was what has already known.

Although, if we see them in the market, the potato -difficult and starch -does not look much like tomato -red and juicy -, “they are very similar, very similar,” Knapp said.

“If you look at the plants, the leaves are very similar, the flowers, although of different colors, also, and if you are lucky to have a potato plant that produces fruits, you will see that it is like a small green tomato.”

Beyond what is seen at first glance, added the taxonoma, “we had long knew that potatoes, tomatoes and ethuberosum were closely related.”

“What we didn't know,” he continued, “was which was the closest to the potatoes, because different genes told us different stories.”

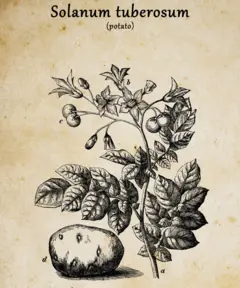

The scientists had passed decades trying to decipher the enigma of the origin of the popular tuber, but they had stumbled upon a difficulty: potato genetics is unusual.

While most species of living beings, including us, have two copies of chromosomes in each cell, the potato has four.

Image source, Thompson & Morgan

To solve the paradox, the team analyzed more than 120 genomes of dozens of species that cover the groups of potatoes, tomato and ethuberosum.

What they found is that the Pope sequenced had approximately the same tomato-eteuberosum division. The ancestor “was not one or the other: they were both,” said Knapp.

Thus they learned of that romance in the skirts of the South American mountains millions of years ago.

It was a tremendously successful union “because it generated combinations of genes that allowed this new lineage to prosper in the newly created habitats of great altitude of the Andes,” he explained.

That was largely thanks to the fact that, although the potato plant on the surface looked a lot like its procreators, there was something hidden that none of them had: tubers.

Having them is like having a lunchbox with you all the time: they store energy, which helps survive winter, drought or any unfavorable condition for growth.

And the scientists discovered something fascinating: they developed them thanks to the gain a genetic lottery.

Image source, Getty Images

It turns out that each of its parents had a crucial gene for the formation of tubers.

None was sufficient on their own, but combined, they triggered the process that transformed underground stems into tasty potatoes.

The Chinese team with which Knapp worked even to verify it, says the taxonoma: “They did many very elegant experiments”, eliminating those genes to confirm their hypothesis, “and without them, the tubers did not form.”

A feat

The hybridization that created the potato was more than a happy accident.

Experts who have commented on the study highlight that this cross between the ancestors of the tomatoes and those of the Etuberosum created a new organ.

And that that organ, the potato, marks a feat of evolution.

Its existence allowed the plant to reproduce without the need for seeds or pollinators.

Thus he adapted to several altitudes and conditions, and expanded, which resulted in an explosion of diversity.

Even today “there are more than 100 wild species, which are only found in America, from southwest United States to Chile and Brazil,” Knapp said.

However, this ability to spread asexually has also played against him.

“To grow potatoes, small pieces are planted, which means that if you have a single variety field, they are essential.

“Being genetically uniforms, they are very susceptible to diseases, because if a new one appears against those who have no defenses, they all suffer the same,” Knapp explained.

This leads us to the reason that led them to do this investigation.

Image source, Shenzhen Agricultural Genomics Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences

Knapp said that the Chinese team “wants to create potatoes that can be reproduced from seeds, in order to modify them genetically more easily, introducing genes of wild species, and thus make varieties that can resist climate change and other environmental problems.”

“I and the other evolutionary biologists in this study, on our side, we wanted to find out who was the closest relative of the potatoes, and why they are so diverse,” he added.

“So we approached the research from very different perspectives and could ask us questions from each of our perspectives, which made it a really fun study in which to participate and work.”

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act..