Image source, Getty Images

-

- Author, Daniel Pardo

- Author's title, BBC World correspondent in Mexico

-

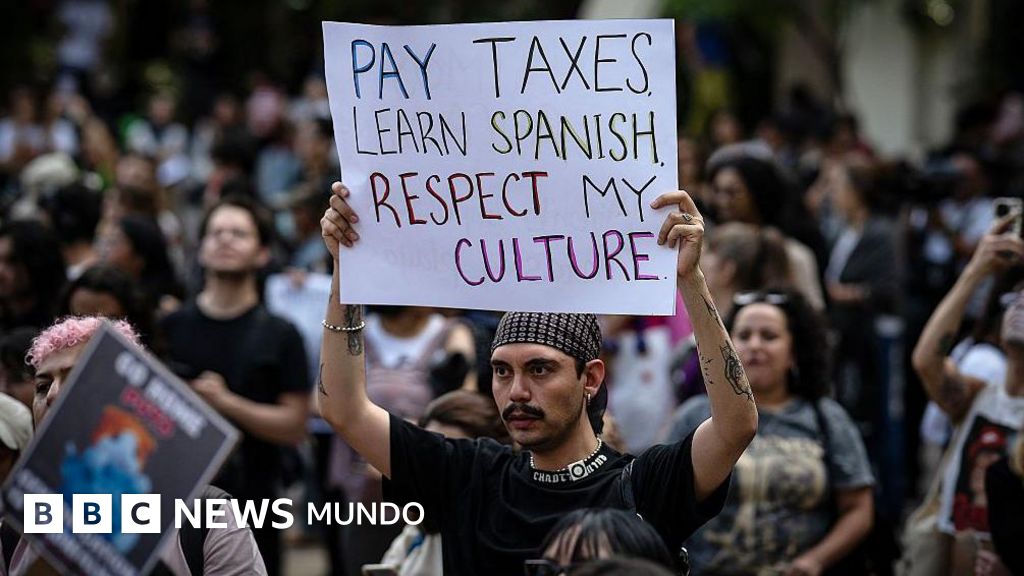

“Tell him not to colonial gentrification,” said one. “Go back to your country, gringo,” asked another. And one more pointed out: “Our identity is not a business.”

The posters in the demonstration against Gentrification in Mexico City last week realized that the claim is not only for the arrival of digital nomads after the pandemic to the fashion colonies of the capital.

The protest, at least a hundred people, most of them young, were held in the most tourist neighborhoods of the city, Rome and Countess, where it is common to see foreigners wandering, walk to their pets and work from bars and coffees.

And in part because the demonstration ended with damage in commercial premises, but above all because there is a sensitive moment of Mexico's relationship with the United States, which initially seemed a timely march of neighbors ended up resuscitating a national background debate on decent housing and tourism, one of the largest sources of income in the country.

The photos of the excesses opened the newspapers. Dozens of columnists and influencers in social networks entered the controversy.

The president, Claudia Sheinbaum, said she rejects “xenophobia” implicit in some of the messages, and two days later added that gentrification is attended with the construction of social housing.

“The standard of living in the city has not to be taken care of in the city and, particularly, the cost of housing and rent,” said the president, who promised to collaborate with the government of the capital, which presided from 2018 to 2023, to promote projects that avoid social segregation.

Image source, Getty Images

The arrival of the nomads

The Rome and the Countess are two of the most coveted neighborhoods of the CDMX for several reasons: they are close to the center, enjoy lush nature that in the rest of the city is scarce, hold a mixture of modern architectural styles and in the last decade they have been repopulated with sophisticated restaurants, naturistic stores and cafes.

The urbanization of both colonies occurred throughout the twentieth century, so both were the epicenter of the different artistic and intellectual waves that passed through the Mexican capital. Until now they were, for the most part, high middle class colonies.

Although the conversion of these neighborhoods at the site of international tourism culture began before – and something will have contributed the Oscar -winning film for the best film in 2018 – during the pandemic thousands of foreigners arrived in search of optimizing their salaries in attractive cities in the developing world.

The CDMX has lived a boom for consumption and openness of new restaurants and bars in recent years.

That gave rise to the last wave of gentrification, that is, to exit from local residents and entry of new projects for tourism.

The difference with this new wave, and with what happens in the dozens of cities that suffer from gentrification, is that in Mexico there is a serious housing deficit, not only in these neighborhoods but throughout the country, which makes their prices more expensive and generates deep social discomfort.

Image source, Getty Images

The increase in housing

To supply the lack of new housing, Mexico should be building three times more residences than it does, according to estimate estimates.

The Federal Mortgage Company, a state fiduciary, reports that the average value of housing in Mexico has grown twice the inflation in the last 10 years.

And, in fact, in the last two years in Mexico City the increase has been less than in the rest of the country, so many wonder if the gentrification of fashion neighborhoods really contributes upwards.

“Gentrification is interflicted,” says Máximo Jaramillo, an expert sociologist in issues of inequality and urbanism. “Because it generates a domino effect, almost epidemiological, which causes the prices of the nearby neighborhoods to raise the market reference tends to be based on the experience of the neighborhoods where the movement is.”

Viri Ríos, a political scientist and analyst, adds: “It is difficult to determine exactly how much the price increase in prices, and the truth is that the increase began before the arrival of digital nomads.”

Both experts, however, emphasize the housing deficit, which in all of Mexico is around 800,000, according to official figures.

And causes of this, they point out, there are many: the monopoly of cement materials in the hands of a couple of protected companies, the high cost of construction permits, the lack of urban planning that prevents the vertical growth of the city and that the recent regulation to short income platforms such as Airbnb, which sought precisely to shorten the rooms, has not been put into practice.

Ríos, director of a Newsletter in English called Mexico Decoded, points about the planning issue: “It was thought that the new generations were going to want to live, like their parents, in the peripheries of the cities under the scheme of the traditional family, and turned out that no, that young people wanted to live in the centers.”

The vast majority of protesters in the recent protests were, in effect, young. “And they are the most affected,” says Ríos.

Jaramillo, director of Gatitos against inequality, a dissemination project, highlights the element of the lack of regulation, not only legal, but financial: “Housing ceased to be seen as a need of rights and became a financial asset that, by design, makes prices increase beyond demand and beyond the needs.”

Image source, Getty Images

To do

The march revived the debate and everything indicates that the authorities are taking note.

The mayor, Clara Brugada, said she will accelerate the implementation of the regulation of short stay platform and initiated assemblies with the affected communities.

And President Sheinbaum referred to her plan, proposed in the campaign, to build a million social homes.

“One of the objectives,” says Jaramillo, “has to be that, to guarantee the right, a percentage of the house leaves the market and that there are tenants with a life contract, for example, so that it cannot be sold.”

Image source, Getty Images

The Trump factor

Another of the things that stood out in the march posters was the presence of Donald Trump and Elon Musk as protagonists of that colonialist barrage that the protesters perceive in gentrification.

“There were two things that, together, are dynamite,” says Ríos, “: the legitimate demand for the regulation of temporary income and climate in the bilateral relationship, which has deepened the feeling of rejection towards Americans.”

Jaramillo coincides: “The historical background is very strong. What we Mexicans have lost and what we continue to lose is huge. Many have relatives in the US hidden, who cannot go to work, by Trump's raids. Rabies is understood.”

The debate on gentrification, or protest in Rome and Countess, ended up being a photo of the past and the present of Mexico.

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.