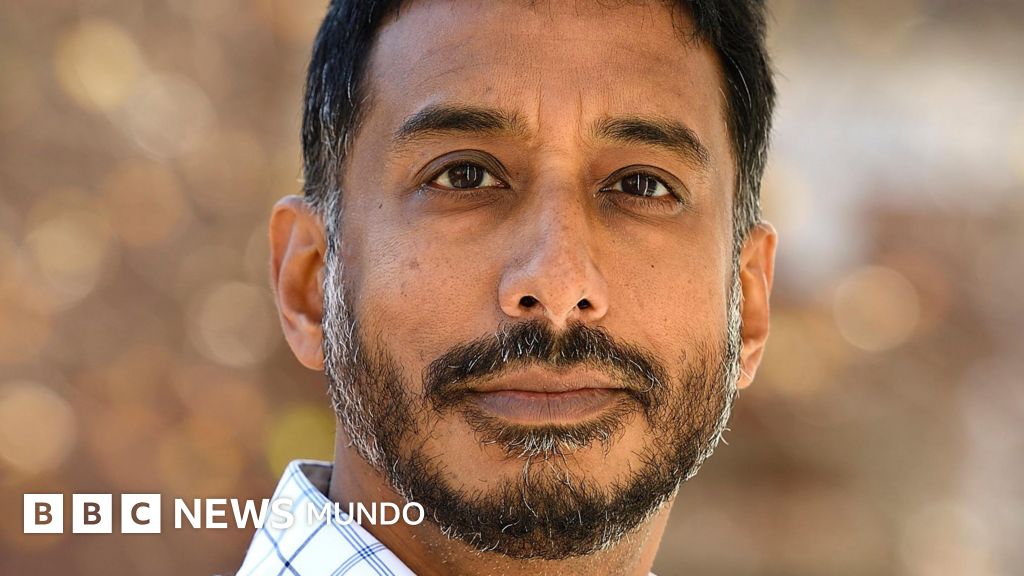

Image source, Gentileza Anand Pandian

-

- Author, Cecilia Barría

- Author's title, BBC News World

Descendant of an Indian family, Anand Pandian was born, grew up and developed his career in the United States.

Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and president of the Society of Cultural Anthropology (SCA), toured his country for eight years to explore the deep cracks that divide Americans into a polarized society.

He was interested in developing informal, intimate conversations, with ordinary people with a different worldview than their own, to understand the reasons that lead them to think as they do.

Pandian found strongly anchored psychological walls in emotions such as distrust, suspicion, restlessness, or skepticism, which tend to isolate people.

With the accumulated experience during his trips, he has just published a book called “something between us: the daily walls of American life and how to tear them down”, where he shares the results of his research.

We talked to Anand Pandian about what he found.

Image source, Getty Images

During the last eight years, the United States has traveled as an anthropologist, trying to understand the psychological walls that divide their country. Because? How did that idea occur to him?

As anthropologists, we pay attention to the cultural life of people, to the social relations that organize their lives. We want to understand the historical, social, and cultural context that lead them to act as they do.

There are many types of walls, such as the walls of our buildings that separate us physically, but there are also metaphorical or psychological walls, such as distrust, suspicion, the feeling of restlessness and skepticism that people usually feel when they hear ideas and stories that are very unknown to them, that do not fit their vision of reality.

Psychological walls such as when we say that others live inside a bubble and do not realize that we also live in our own bubble.

Yes, it is true we live in our own bubbles and one of the main reasons why I decided to do this job is because I wanted to think and imagine the country beyond my own bubble.

When Donald Trump won the elections in 2016, I understood that there were many people who thought differently, who had other positions, and as an anthropologist I needed to understand how we came to this situation, especially in migration issues, in the sense of whether there really is there really room for people from various origins.

When exploring this situations, I came to see again and again how much people were really isolation in their daily lives.

Image source, Getty Images

Would you give me an example that represents that isolation?

I saw it in the closed residential communities that have become so common in this country and in all the security technology that replaces face -to -face meetings with strangers. The bells with camera as an alternative to simply open the door when someone hits.

There are daily habits that reflect isolation, such as using less streets and spending more time only with acquaintances, or depending on increasingly large cars designed to protect themselves from possible danger.

I came to understand that all these habits of protecting, separating, of isolation, have a lot to do with those ideas that seem to have captured the imagination of so many Americans. And that is the story I try to tell in the book.

During all these years that the country was touring, what was the most unexpected experience, the one that had a greater impact on a personal level by relating to people who have a different worldview than their own?

It was a very interesting experience because I discovered very different reactions between people with a worldview different from mine, with political ideas other than mine, with very different ways of understanding what the country needs and who we are as Americans.

I was surprised that some people were much more flexible than I expected and very willing to talk to me, to reflect on our ideas and to explore the differences between our opinions, sometimes reaching an agreement.

I think, for example, one of the characters about which I write in the book, Paul, a North Dakota Properties Corridor.

He is a life of a lifetime, very committed to the positions of that party, but on the other hand, he was also a defender of soil and water conservation, and also had very different positions to those of his party on issues such as migration.

It was a pleasant surprise to see that someone with whom perhaps did not expect to have much in common, in the end, he had a much more nuanced position and, well, there was simply much to talk about.

Image source, Getty Images

And how was the experience with those most uncompromising?

I also met people with whom there was nothing we could share. We couldn't reach any agreement. There was no way to find points in common and, in those cases, hope was simply to understand why our divisions were so deep.

An example of this would be the person I call Frank in the book, a little businessman from a town in southern Michigan. I met him at a libertarian conference in Las Vegas, visited his people and spent a few days there.

He visited me in Baltimore and we were in contact for several years, during which we discussed a lot, especially at the time of the pandemic, about issues such as vaccines and the need to use masks, or about the country's policy, economy, migration, and so many more things. But, in all cases, we had radically different perspectives.

And what I try to show in the book is how our own media ecosystems, where we get our information and how we develop our own sense of reality, greatly influenced the impossibility of that mutual understanding.

Speaking about the difficulty of agreeing, how was your experience with white nationalists in Tennessee?

I went to a white nationalist demonstration in Shelbyville, Tennessee, where people argued that the different races could not, simply could not, live together, and advocated the idea of dividing the United States into a series of ethno -state where each race would have their own country.

Image source, Getty Images

Was that the most extreme vision he found during his trips?

It is that the purpose of the book is not to focus so much on the extremes, but on seeing how extreme ideas can be normalized so easily.

In a way, I would say that these forces of isolation, suspicion, distrust, skepticism in our society, have been integrating into our daily lives.

So, in many ways, the book is about what we have come to understand as normal and what can happen when radical insulation and separation circumstances become normal for so many people.

This project is about isolation and tries to understand why isolationist policy has become so powerful in this country, to the point that people imagine completely isolated from the rest of the world and those who are not like them.

And the conclusion I reached is that we cannot understand political isolationism without analyzing daily isolation.

Image source, Gentileza Anand Pandian

How can you reduce isolation and social polarization, especially now that a political narrative has extended that divides people between allies and enemies, which revolves around hatred?

It has to do with how we understand the foundations of social exclusion and discrimination.

I think we tend to think about hate, which is a very strong and active emotion. And there is certainly evidence of hate in this country.

But just as dangerous, and in a way even more dangerous, because it is difficult to see, it is indifference. The indifference of not worrying at all about other people, not paying attention, not realizing. And in many ways, this is a book on the effects of indifference.

On the other hand, what I learned through this research is that there is a real difference between the walls that reject any relationship with people from abroad and the most open and porous walls that still allow the possibility of a relationship with places, people and ideas that are alien to us.

We need that kind of openness if we want to discover how to live together in the world. And here, I think, it is where that psychological dimension becomes great importance.

While we have many insulating trends, we also have the experience of social movements that have focused on joining people, creating unexpected alliances and finding ways to live together.

Image source, Getty Images

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.