Image source, Getty Images

-

- Author, Writing

- Author's title, BBC News World

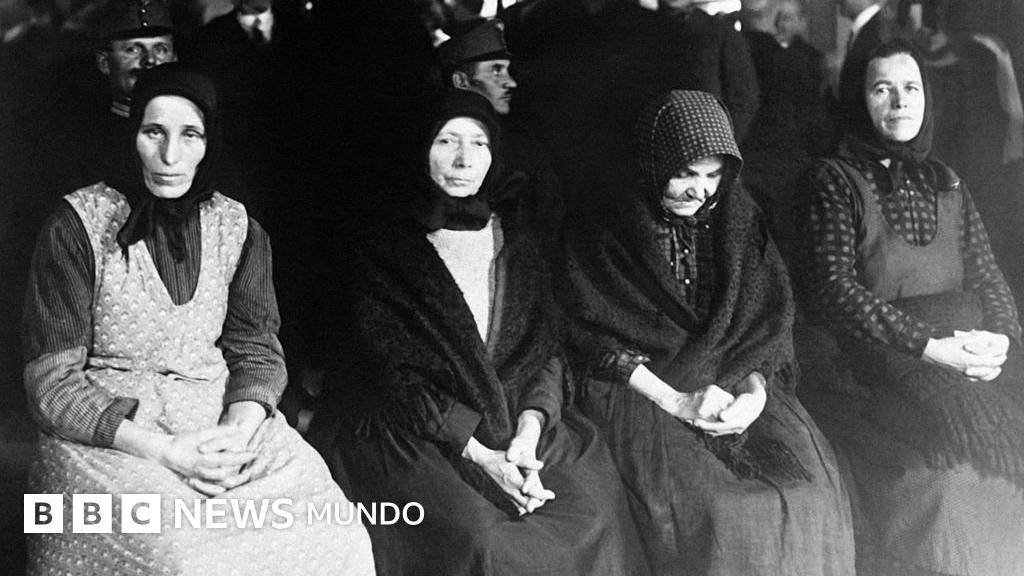

On December 14, 1929, the American newspaper The New York Times He made a review of a news that was causing stupor not in the US, but much further, in Hungary: a trial began about 50 women who had been accused of poisoning the vast majority of men who lived in a remote town in the European country.

Although the review was short, the story had many details: between 1911 and 1929, several women from the Nagyrev town, located about 130 kilometers south of Budapest, would have poisoned more than 50 men.

The women were called the “angels” and would have killed men with an arsenic solution.

Some have described it as the greatest mass murder of men by women in modern history.

The women faced a public trial in which there was a name that was repeated: Zsuzsanna Fazekas, the midwife of the people.

In those times, when the people were still under the dominance of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and there were no local doctors, the midwife had the medical monopoly of the town.

In 2004, in a radio documentary of the BBC, Maria Gunya, who lived in the town, said that the reason he was pointed out to Fazekas as the inciter of poisoning, was because all women told him his problems.

“He told women that if they had problems with her men, she had a simple solution,” Gunya explained.

And although Fazekas remained as the main responsible for the murders, in the archives of the process, the testimonies of the women of the people reveal deep and painful stories of abuse, abuse and rapes by men.

But the story was hidden for many years. According to police reports, the first murders were recorded in 1911, but it was not until 1929 that investigations began.

What was the track that allowed the culprits to reach? A cemetery that began to be filled suddenly.

Image source, Getty Images

Other times

In 1911 the population of Nagyrev came Zsussanna Fazes.

She, according to Gunya and the testimonies of the trial, caught attention for two things: first because, in addition to her ability as a midwife, she was aware of medicinal remedies, some even with chemicals, something unusual in the region.

The second was that there was no trace of her husband.

“Nagyrev had no priest, much less a doctor. Then his knowledge made people approach her and take confidence,” Gunya said.

“The woman began to see many things that happened inside the houses: men who beat women, who raped them, many of them were unfaithful. A lot of abuse,” he added.

Then Fazekas began to perform a prohibited practice at that time: clinical abortions of unwanted pregnancies. For this reason she was taken to trial, but was never convicted.

The big problem, says Gunya, is that many marriages were agreed by very young families and women married men, in some cases, much older.

“At that time there was no divorce. You couldn't separate even if they mistreated or abused you,” he said.

But the reports of the time also pointed out another fact: the agreed marriages were accompanied by a kind of contractual agreement that included land, inheritance and legal obligations.

“Fazekas began to convince women that she could solve their problems,” Gunya told the BBC.

The first poisoning occurred in 1911. In later years they continued to die more and more men, while the First World War was developed and the Austro-Hungarian Empire crumbled.

Image source, Getty Images

In 18 years, they occurred between 45 and 50 deaths of husbands and parents who were buried in the town's cemetery.

Many began to call Nagyrev “The District of the Killers.”

These details caught police attention. At the beginning of 1929 the bodies began to exhume to examine them, finding an incriminating element: arsenic.

Judgment to women

Fazekas lived in a typical one -floor house in the town, with a view to the street. It was there that he created many of the poisons that were used in the murders.

There, on July 19, 1929, he saw that the police came for her.

“When he saw the gendarmes approach, he understood that everything had ended for her. By the time they arrived at the house, he was already dead; he had taken a little of his own poison.”

But the midwife was far from being the only guilty.

In the nearby capital of Szolnok County, as of 1929, 26 women were tried.

Eight were sentenced to death and the rest were sent to prison, seven of them for life.

Few admitted their guilt, and their motives were never completely clear.

Based on the courts of the court, the doctor and historian Geza CSEH told the BBC that there are still many mysteries to resolve.

“As for their reasons, theories abound: poverty, greed and boredom are some of them,” says the academic.

“Some reports say that some women had had lovers among Russian wars recruited to work on farms in the absence of their men in the front,” explained the historian.

And when the husbands returned, the women regretted the sudden loss of their freedom and, one after another, they decided to act.

Image source, Getty Images

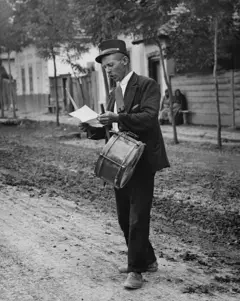

In the 1950s, historian Ferenc Gyorgyev met an old man from the town during his imprisonment under the communist regime.

The peasant said that Nagyrev's women “had been killing their men since time immemorial.”

In addition, perhaps they were not the only ones.

In the nearby city of Tiszakurt, other exhumed bodies also contained arsenic, but no one was convicted of these deaths.

According to some estimates, the total number of dead in the area could have promoted 300.

Gunya points out that, after poisoning, the behavior of men with their wives “improved significantly.”

Image source, Getty Images

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.