To say that the last five decades of parliamentary history in Spain have passed through the hands of Ana Rivero would be inaccurate. This recently retired stenographer of the Congress of Deputies not only wrote down each and every word spoken by the speakers, but was able to savor every historical moment that occurred before her, smell the tension that was often experienced in the chamber and touch with her eyes the astuteness, serenity and, sometimes, grandiloquence with which the parliamentarians speak.

Now, set aside the Session Log to publish Light and stenographer. Fifty years transcribing the History of Spain (Plaza y Janés, 2025), where he reviews the vicissitudes that he has had to experience for so long, and that have not always left a good taste in his mouth. From Franco's black and white courts, as she herself describes, her work activity has overcome a coup d'état, motions of censure, parliamentary debates that will go down in history, the approval of rights that have changed the future of the country, successful and failed investitures and even a coronation.

“I came to Congress because one year I failed stenography and my father, who was a stenographer and then a cryptologist, told me that that couldn't be the case,” Rivero says with a certain grace in front of the lions that guard the Lower House. Together they worked to improve the academic results of this woman from Madrid born in 1954. Barely at the age of 18 he began to take the exams, which he always passed, until at the age of 21 he was able to join the Corps of Stenographers and Stenotypists of the Cortes Generales. It was May 1975 and the Cortes woke up full of somewhat taciturn, deified men, surrounded by a dictatorial aura clouded by tobacco smoke, not at all accustomed to debate or consensus.

At that time there were so few parliamentary committees that, if they needed more stenographers than usual, they used those who studied at the academy located in Congress itself. “I had a terrible time in those Francoist Courts. Great luck came with the Law for Political Reform, which later gave way to the Constitution,” he recalls in reference to the first law approved in 1977.

The other Bar Chicote, the other constitutional negotiation

Throughout her book, written with Ana I. Gracia, also a parliamentary stenographer since 2021, Rivero covers some of the scenarios normally prohibited for the general population but that she, due to her job, was very aware of. This is the case of Bar Chicote, but not that of Madrid's Gran Vía: “It was a bar inside Congress that existed since the Second Republic, now gone. It was in the room that opens if you enter through the main door, the one with the lions,” he says.

At those tables the “Unofficial Commission in which the Constitution was unstuck” was formed, as Rivero calls it in his monograph. “Every time the constituents did not agree on a point, the debate continued at Bar Chicote, and I kept seeing the leaders of each party negotiating their positions,” he emphasizes. Finally, something so curious was suppressed after Gregorio Peces-Barba assumed the presidency of Congress in November 1982. “The truth is that it smelled a lot like croquette and chorizo, but it was something very curious,” remembers the stenographer.

Somewhat less pleasant have been other passages in Spain's recent history that have also touched it closely. Rivero, when he arrived at Congress on February 23, 1981, could not even imagine what would happen hours later. “He caught me at the door of the Hemicycle, because they wouldn't let me enter to relieve my partner. A very young civil guard told me that there were ETA members in the stands,” he details. The worst omens rushed into his thoughts: “I went back to the office and told my boss. When we heard the shots we thought our colleagues might be dead. It was a very difficult moment and I thought 'how short democracy had lasted us'.”

Cases of sexual harassment: “They could make my life impossible”

Despite what anyone might think about Congress, there are phenomena that do not differentiate it too much from other workplaces. 'The day a deputy tried to kiss me' is the chapter that Rivero dedicates to two disastrous experiences related to sexual harassment by a pair of parliamentarians. “I have never said their names and I am not going to say them, although one is already dead, but I did want to leave testimony that harassment situations also occur in Congress,” he asserts.

I wanted to testify that harassment situations also occur in Congress. As a civil servant they couldn't fire me, but they could make life impossible for me or my family, so I kept it quiet.

She assures that the protagonists of the attacks were politicians from both the right and the left and that the episodes occurred when she was 30 and 50 years old. “I had a very bad time. I was aware that, as a civil servant, they couldn't fire me, but they could make life impossible for me or my family, so I kept it quiet until now, when I tell it in the book,” the stenographer explains.

The first of them, according to Rivero, did not respect his refusal to meet him outside of Congress. “He wanted me to go to lunch with him, to dinner, to everything; and he called me on the phone at dawn, at all hours,” he remembers. The second was something different. Rivero had helped him with the correction of some of his books: “When I agreed to have coffee and take a walk with him, he cornered me in the Prado Museum,” he says.

After half a century listening to debates about laws, rights and obligations, the stenographer defends that no right won lasts forever. “Abortion, divorce, equal marriage are rights that will always have to be defended, just like democracy, which must always be deepened,” he maintains. Beyond transcribing every word uttered by parliamentarians, Rivero has always felt the emotion of each historical moment. As he highlights, it happened with the approval of the voluntary interruption of pregnancy. “As a woman, I was very happy. How many women have died from having to go to England or have suffered atrocities in clandestine abortions?” she asks.

The drowsiness and pleasure of listening to parliamentarians

Her extensive background translating words into symbols that only she understands on the only table with legs inside the chamber has led her to know well which speakers to pay more attention to than others, always on a personal level. “There are some who put the sheep to sleep, you see them and you don't want to go into the shift, but others are so interesting that when you leave you go up to the stands to continue listening to them,” he illustrates.

He especially remembers Joaquín Viola Sauret, whose one of his speeches was the one with which he was examined. “He was a machine gun talking. At that time he was already defending that people with names in Catalan could be registered in the civil registry, and he achieved it,” he adds about this former mayor of Barcelona who was brutally murdered in January 1978 along with his wife in an attack attributed to the National Front of Catalonia.

Conciliation, something impossible for stenographers

The working conditions in which this Corps of Stenographers, highly feminized, has historically been forced to perform its functions deserve a separate chapter. “It was impossible to reconcile. We are the only body in Congress that does not have a fixed schedule. If your honors want to hold a session on Three Kings Day or in the middle of Holy Week, you have to be there. How many hours will you have to work? Whatever they decide,” she answers herself.

The situation has changed a lot in recent years thanks to the rationalization of work: “When I started, if you wanted to get married it had to be in the summer. They almost opened a file for me because at Christmas several of my traveling companions went to India and a minister wanted to appear on December 30.”

After all, the stenographers are responsible for the Session Diary, which with unusual agility is published daily on the Congress website. “It is an official document that Congress has published since 1810, more than two centuries ago, and in which it must literally contain everything that the deputies say,” defines the specialist.

In this sense, they must be very careful to try to touch the speaker's words as little as possible, but make their speech intelligible. “They even use it in judicial processes because the judges review it to see clearly what spirit the legislator has followed when approving a law. It is also a good document to see how the debates and conflicts that concern society evolve,” he adds.

A wonderful life ahead

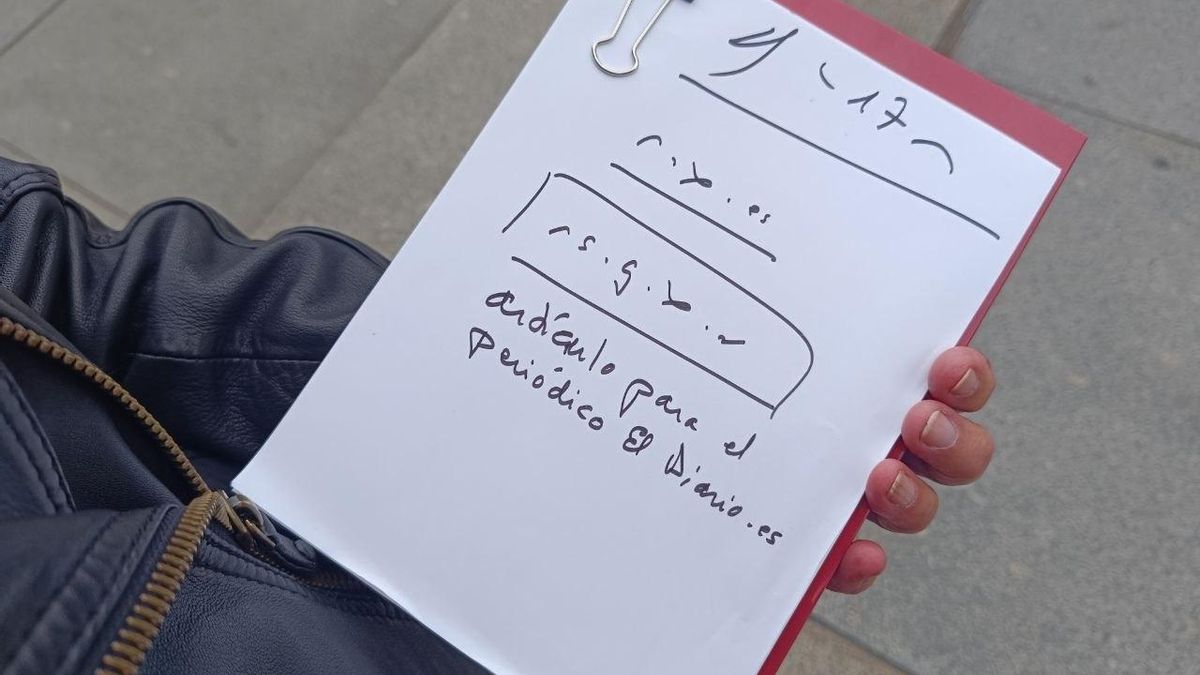

Rivero has created his own language that, although retired, always accompanies him. “My father also taught shorthand to my brothers, but in order to catch up to parliamentary speed I have had to design my own system. Even though they have the same method, my brothers are no longer able to understand what I write,” he explains.

And he continues to use it. This is demonstrated by his latest notes from a university course he is taking these days. At 70 years old, Rivero faces a wonderful new life, as she herself emphasizes, which will allow her to travel much more than she has already done, which has not been little either. “My concerns accompany me, and that always gives life,” he says goodbye.