Image source, APG/Mondadori Portfolio Archive via Getty Images

-

- Author, Myles Burke

- Author's title, BBC Culture*

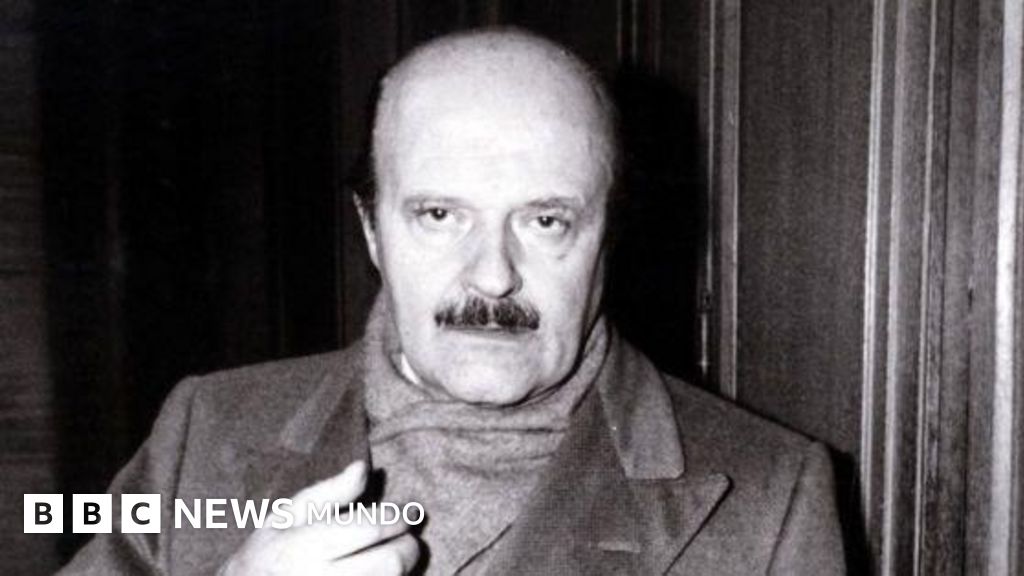

Forty -three years ago this week, the BBC reported on the death of Roberto Calvi, an Italian banker whose body was found in strange circumstances in downtown London. His bank was linked to the Vatican, a Masonic group and the mafia, and his murder left many unsolved questions.

Roberto Calvi was the president of the prestigious Ambrosian Bank, the largest private bank in Italy. He was so closely linked to the Catholic Church that he was known as “the banker of God.”

But on June 18, 1982, Calvi, 62, died and his body was discovered hung under the London Blackfriars bridge.

“Calvi was in the center of an incredibly complex network of international deceptions and intrigues,” said Hugh Scully of the BBC.

“It involved the Italian banking world, the underworld, the mafia, the Freemasonry and, above all, the Vatican.”

The death of the banker would trigger a huge political and financial scandal in Italy, which would imply the disappearance of millions of dollars and leave behind a lasting mystery.

Image source, APG/Mondadori Portfolio Archive via Getty Images

Calvi had been missing for nine days when they found him hanging from a scaffold installed under the London bridge.

And it was the strange circumstances of his death that bold the British police.

His pockets were full of bricks and carried about US $ 14,000 in cash in different currencies.

He also had a false passport with the name of Gian Roberto Calvini.

Despite these circumstances, the initial forensic report of July 1982 found no clues in his body that suggested criminal activity, so it was determined that the banker had removed his life.

But at that time there was suspicion that there was something much darker.

“Calvi's last trip was not that of a man who intends to commit suicide,” said Scully. “In fact, he had to build elaborate plans to leave Italy in secret.”

The banker had shaved the mustache to avoid being recognized and had concealed his exit route from Italy passing first through other countries and hiring a private plane to take him to London.

“I had a rental contract for a month in an apartment in Chelsea and then there was a false passport and a plane ticket,” Scully said.

Within the passport there was a valid visa for Brazil and the plane ticket was only first leg to Rio de Janeiro. Why get so far to finish hanging from a rope under the Blackfriars bridge?

Image source, Ken Goff/Getty Images

Calvi's was not the only death at the Ambrosian Bank. The day before his body was found, his personal secretary, Teresa Corrocher, apparently had also jumped from the fourth floor of the bank headquarters in Milan.

He left a note condemning his boss, writing that he should be “punished twice for the damage caused to the bank and all his employees.”

Calvi and his bank had operated in a murky world in which finance, organized crime, politics and religion were superimposed.

Founded in 1896, the Ambrosian Bank had a long history with the Catholic Church, and the Institute for Works of Religion (IOR), often known as the Vatican Bank, had become its main shareholder.

The IOR maintains the bank accounts of the Pope and the clergy, but also manages the financial investments of the Church. As the Vatican is their own country, Italian regulators do not have control or supervision about the IOR.

Mafia connections

Image source, Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“The Vatican is completely free of change controls and other government regulations; the secret is everything,” said Scully.

The Vatican does not have to account for anyone for their financial operations, and huge sums of money can be sent anywhere in the world without anyone knowing, except those directly involved.

Through his role as head of the Ambrosian Bank, Calvi forged narrow links with his counterpart in the Ior, Archbishop Paul Marcinkus.

In turn, this American priest had financial connections and partners that raised many suspicions.

“The most recognized was Michele Sindona, an international banker with connections with the mafia that now celebrates a 25 -year prison sentence for fraud in the US,” Scully said.

Sindona, known in the bank circles as “the shark”, would be subsequently transferred to a prison in Italy, where he would find his own final in 1986, after drinking coffee contaminated with cyanide.

Image source, Reg Lancaster/Express Newspapers/Getty Images

Sindona had Calvi as a mentor in his banking career since the end of the 60s, and both belonged to a dark Masonic lodge called Propaganda Dos (P2).

The group was linked to extreme right organizations and was directed by the multimillionaire and famous Italian fascist Licio Gelli.

It had among its members with prominent figures of the military, political, business and journalistic field.

An Italian journalist, Count Paolo Filo Della Torre, told the BBC in 1982 that although the P2 was in theory a Masonic lodge, “in practice it was something closely associated with the mafia and with all kinds of dirty treatment.”

In March 1981, the Italian police raided Gelli's offices and discovered in a list of hundreds of alleged members of the P2, including politicians, military officers and the media magnate and future Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Revelation caused a political scandal. Italian prime minister, Arnaldo Forlani, and all his cabinet resigned; A police chief shot and a former minister was transferred to the hospital after suffering an overdose.

Police raids managed to discover compromising documents that involved Calvi in fraudulent practices and illegal operations on the high seas.

In May 1981, the banker was arrested and declared guilty of monetary violations. He was sentenced to four years in prison, but was released on bail pending an appeal.

Calvi took the opportunity to get out of the country with a briefcase full of documents on the illegal activities of the Ambrosian Bank. A few days after his arrival in London, his bank broke, leaving behind huge debts.

Thousands of missing millions

Image source, Adriano Alecchi/Mondadori Via Getty Images

“Before Roberto Calvi disappeared, Italian investigators discovered that US $ 1.5 billion of their bank's dollars were missing,” said Scully.

“Now it is believed that this money was sent abroad through the Vatican Bank, which evades the Italian exchange controls. Part of that money was sent to South American countries with low interest rates, according to the provisions of the Catholic Church. The rest was invested in ghost companies in Luxembourg and South America, from where he returned to Italy to buy Calvi shares at the Ambrosian bank.”

Marcinkus was also sought to interrogate him, but he was granted immunity as a Vatican employee and maintained his innocence about any irregularity.

The Vatican never admitted any legal responsibility for the collapse of the Ambrosian Bank, but in 1984 he said that he had a moral responsibility for failure and made a voluntary contribution to the bank's creditors of US $ 406 million.

The researchers believed that the ghost societies that Calvi had created were used to move money both to support secret political activities in other countries and to launder money for clients and the mafia.

“Police investigations on Calvi 'affairs threaten many powerful people in Italy and some believe they provided a reason for their murder,” said Scully.

Image source, ANDREAS SOLARO/AFP via Getty Images

Filo Della Torre, who knew Calvi, told the BBC in 1982 that he believed that the banker had been killed and that the fact that his body had been abandoned under the Blackfriars bridge had a Masonic symbolism.

He said that P2 members wore black robes in their meetings and referred to them as “frati neri”, which in Italian means “black friars.” When Scully said this made Calvi's death seem “something taken from the Borgia,” the Italian journalist replied: “I'm sorry. We are returning to an entire Italian tradition.”

Calvi's family also refused to accept the conclusion of suicide, revoked in 1983 when a second investigation issued an open verdict on this death.

But his family, including his widow, Clara Calvi, kept the police investigating, and hired their own private investigators and forensic experts to investigate the death of the banker.

After Calvi's body was exhumed in 1998, new evidence was obtained against the suicide hypothesis.

Forensic evidence showed that the neck injuries were not compatible with a death due to hanging and that Calvi's hands never touched the bricks in their clothes. In October 2002, Italian judges concluded that the banker had been killed.

The Italian police initiated an investigation and in October 2005, 5 people were accused in Rome of Calvi's murder.

The prosecutor, Luca Tescaroli, argued that the banker was killed for stealing money from the mafia for his own benefit, and that Calvi planned to blackmail other influential people, including politicians.

In June 2007, after a trial that lasted 20 months, the banker Sardo Flavio Carboni, his ex -girlfriend Manuela Kleinszig, the Roman businessman Ernesto Diotallevi, the bodyguard of the chauffeur of Calvi Silvano Vittor and the convicted treasurer of the thing Nostra Pippo Calo – which he fulfilled two perpetual chains for crimes of the mafia – Calvi's death.

It is still speculated who ordered and finally carried out the murder of the Italian banker. To date no one has been convicted.

This is an adaptation to the Spanish of a story originally published by BBC Culture. If you want to read it in English, do Click here.

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.