Image source, Graham Poulter

-

- Author, Writing

- Author's title, BBC News World

“It is my favorite. Excuse the smell. It is formalol.”

British scientist Alexandra Morton-Hayward holds in her hands one of her most precious objects.

It is a brain to which “Rusty” nicknamed (“ahterrerorado”). The brain, shrunk and reddish, looks small in the expert's gloves.

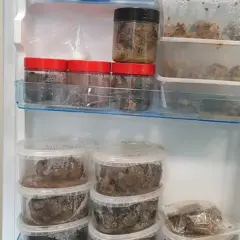

Morton Hayward is forensic anthropologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford, where he takes care of two extraordinary exemplary refrigerators.

The scientist has gathered a collection of more than 600 old brains from different parts of the world, some with up to 8,000 years old. “I don't know another major collection,” he said.

The brain usually breaks down quickly after death. How is it possible then that they have been found in brains archaeological sites that did not succumb to that degeneration process?

It is a mystery that baffles scientists and that Morton-Hayward tries to unravel. The answer, he says, could help study neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson.

But the first time Morton-Hayward saw a human brain was not in a laboratory.

He worked at a funeral home, and had interrupted his studies due to a painful condition that continues to mark his life and originates in his own brain.

Image source, Gentileza Alexandra Morton-Hayward

“The most painful condition known to humanity”

Morton-Hayward studied archeology at St. Andrews University in Scotland when he began to suffer unbearable headaches.

“I remember crying a lot, not only of pain, but also of confusion. I did not understand why what was happening to me,” he told the BBC.

The young woman had to leave the university, returned to live with her parents and sought a succession of jobs, including a job at a funeral home.

The doctors, who for years did not find a cause for their illness, finally diagnosed a condition called cephalea in clusters, a type of headache marked by intense episodes or clusters that usually last between 30 and 60 minutes.

“According to a study Of 2020, the headache in clusters is the most painful condition known to humanity: it is qualified with a 9.7 on a pain scale from 0 to 10. To contextualize, giving birth occupies the second place with a 7.2! “The scientist explained to the BBC.

“It's hard to imagine giving birth three times per night and getting up to work the next day, but for me that is normal.”

Image source, Alexandra Morton-Hayward

Archaeological findings

Despite his fragile health, Morton-Hayward enrolled in 2015 in online classes at the Open University or Open University to finish his degree.

He graduated with Honors and in 2018, while he still worked at night at the funeral home, a master's degree in bioarcheology and forensic anthropology at University College London (UCL) began.

It was during his postgraduate studies that ran into a rarity that would change the course of his life.

Years before they had been found in perfectly preserved brain archaeological sites.

In 1994, for example, archaeologist Sonia O'Connor had examined remains excavated in Hull, in England, where about 250 tombs of a medieval monastery were exhumed.

Nothing prepared archaeologists for the moment a skull broke, revealing a brown mass with superficial folds.

It was the brain of someone who had been buried more than 400 years ago.

Image source, Gentileza Alexandra Morton-Hayward

What happens in the brain after death

After death, brain enzymes begin to consume cells from within, a process called autolysis. In a matter of days, cell membranes break and the brain is liquefied.

Morton Hayward remembers the first time he saw a brain in these conditions, when he worked at the funeral home.

The deceased person had been practiced an autopsy. And next to the body a plastic bag containing the organs examined was sent to the funeral.

“I clearly remember the surprise that caused me to see that the brain had disintegrated,” said the researcher.

Scientists still do not know certainly why some brains can last hundreds or thousands of years.

Morton Hayward, however, has a hypothesis: the same molecular processes that damage our brains in life could help preserve them after death.

Image source, Graham Poulter

Ancient brains and keys to dementia

“In essence, everything begins with the decomposition of fats as the brain deteriorates: fats contain long chains of carbon atoms, and when decomposing they are fragmented and react with other nearby molecules joining them,” Morton-Hayward explained to the BBC.

“In the brain, rich in both fats and proteins, these 'cross -linked' fragments are added and agglutinated, which, ironically, makes them more resistant to greater decomposition.”

This process of agglutination of lipids and proteins in life is accelerated in the presence of metallic ions and the brain is rich in them, adds the expert.

A certain amount of iron, for example, is essential for a healthy brain function.

But iron accumulates naturally in the brain with age and does so at an accelerated pace in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Morton-Hayward explained.

The same accumulation of iron that catalyzes the agglutination of proteins and lipids, and the aging and degeneration processes, also makes the brain resistant to decomposition.

“It is known that the abnormal accumulation of certain proteins contributes to the development of certain neurodegenerative diseases, forming plaques that interfere with the normal functioning of the brain. The thousands of ancient brains preserved in the archaeological registry have similarities with this type of pathology, and could even be formed by some of the same mechanisms,” said the researcher.

“Studying ancient brains as the extreme point of the aging trajectory that we experience throughout life could help us understand the development and progressive nature of dementia.”

Image source, Alexandra Morton-Hayward

Suffering in life

Something that surprises Morton-Hayward is that many of the ancient brains come from people whose lives ended traumaticly: in common graves, violent deaths or asylums in conditions of extreme poverty.

The scientist believes that there is a significant link between that trauma and the excessive presence of iron.

“Iron accumulates in the brain as we get old. We get old faster if we suffer deprivations, traumas, stress, etc. Therefore, more iron is expected to be in the brain of those who have suffered.”

It is the presence of iron that explains, for example, the reddish color of Rusty, the favorite brain of the scientist.

“A lot of iron has been found in archaeological brains that does not seem to come from the funeral environment, so it perhaps accumulated in life and, being such an excessive amount, could suggest that these people suffered,” said the researcher.

“Any type of physiological stress, such as starvation, for example, ages faster and can make death come before.”

“Maybe that's why we have so many brains from places where there was suffering and deprivations.”

A file of more than 4,000 brains

The survival of the brain between skeletonized remains, in the absence of other soft tissues, was considered until recently an extremely rare phenomenon.

But Morton-Hayward and his colleagues in Oxford showed otherwise.

In a study Published last year in the Royal Society B minutes, a magazine of the British Academy of Sciences, the Forensic Anthropologist and other researchers compiled a new archive of ancient human brains, the broadest and most complete archaeological literature to date.

Scientists recorded more than 4,000 human brains preserved on six continents (excluding Antarctica).

Some of them have an age of up to 12,000 years and were found in a wide variety of archaeological deposits, including the banks of the bed of a lake in Sweden in the stone age, the depths of an Iranian salt mine around 500 BC. C. and the top of Andean mountains in the apogee of the Inca Empire.

Image source, Alexandra Morton-Hayward

“I have learned to live with this”

In his effort to decipher the molecular processes that occur after death, Morton-Hayward has brought brain tissues even to the syncotron Diamond Light Source in Harwell, England, the National Particle Accelerator of the United Kingdom.

There bombarded brains from his collection with electrons that were traveling almost at the speed of light to identify the metals, molecules and minerals present.

While investigating ancient brains mysteries, Alexandra Morton-Hayward continues to learn to live with his.

“I use medication and meditation to cope with headaches, and there is no way to work during an attack, that is safe! I also find my cat very reassuring (it's called Atlas, because my world holds).”

“But what allows me to continue with my day to day is, ironically, the other face of pain itself: I have often discovered that pain is so intense that it is almost as if the body refused to store it in memory. One of the many amazing things of the mind, I suppose: its capacity for self -protection,” the scientist told the BBC.

“I have learned to live with this (although, of course, a few days are harder than others, as for all). And the days when I feel that my brain works with me to vary, instead of against me, that reminds me how extraordinary this organ is.”

Alexandra Morton-Hayward spoke with BBC Mundo and with the Radio Outlook program of the BBC World Service.

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.