-

- Author, Daniel Pardo

- Author's title, BBC World correspondent in Mexico

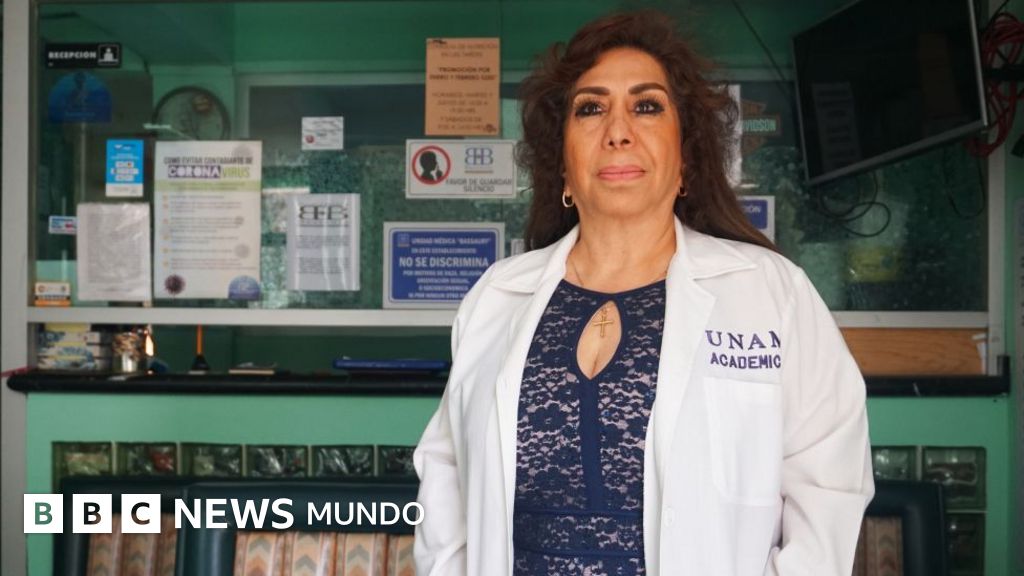

The Bassuary Medical Unit, east of Mexico City, in the immense municipality of Nezahualcóyotl, is not a usual clinic: it is in a residential house, it has altars in each corner and in the office of Dr. Chief, Sarahí Hernández, more than diplomas there are photos: of it when young, of Pedro Infante, of his patients.

“I like to see people in the face, touch them, give them the apapacho that we need so much,” says the 58 -year -old doctor. “People have come to me with a rotten foot, literally, smelling ugly, and I can not do anything other than to move, treat them and help them. Because you imagine if the doctors only serve the beautiful people.”

The Bassuary -whose name is a meeting of the initials of his father, mother and brother; All doctors- is, in its terms, a “particular clinic.” And familiar.

It is not in a building built to be a hospital, but it provides many of its services: emergencies, surgery, consultation.

In Mexico they are usually called “Duckling Clinics”, a pejorative term that connotes informality, illegality, medical malpractice. But Bassuary, as well as many of these private clinics, not only comply with regulation, but sometimes give a service that traditional hospitals may not.

Services such as Apapero: Nahuatl word for love, comfort, hug, palmadita.

And above all to those who need it most: for example, the migrant population, which these days, says Hernández, “seem to have gone, but there they are, they will return, because their situation is very difficult and here we are here to help them.”

Today migrants are 10% of Hernández's patients, but a few months ago they were more than half.

Image source, Getty Images

After the arrival of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States, the migrant flow in Mexico seems to have been reduced or changed on course, with what spaces of attention like this, or the shelters, are half empty.

The same, says the doctor, “we have more than 300 patients, because need is what there are and hospitals is what there is almost no,” he says with irony.

Solution for a collapsed system

In virtually all Mexican states, it is common, especially in the peripheries of cities, that health demand is partially supplied by spaces like this.

Some are exclusive to older adults, others for outpatient treatments: the portfolio of specialties and coverage levels is large.

The Bassuary lends a little of everything, but its existence, admits Hernández, has a lot to do with the shortage of the public health system.

“Neza has only two hospitals and very few censors; without our support it is impossible to supply,” he says.

The Mexican public health system is in crisis decades: there is inequality in access, shortage of medicines, corruption scandals, among other factors.

“Only in Pandemia – says Hernández – I attended 14 thousand patients, by phone, by chat, in person. A hospital has 70 beds, the other 300. And they were collapsed.”

To the crisis in the sector it is added that the Mexican population suffers high rates of obesity, hypertension, diabetes and gastrointestinal infections.

But for the migrant population the situation is even more difficult, because they come from a tortuous trip through several countries and face the bacterial and food complexity of Mexico.

“For almost all (migrants), the first problem is intestinal. Not only because here food is irritating and greasy, but because water has other bacteria,” says Hernández.

But other cases are even more serious. She remembers a migrant who arrived with a clavicle fracture because the coyotes had thrown her from a bridge.

Image source, Private archive

A migrant who visited the clinic is Vanessa Alejo, a 29 -year -old Venezuelan who met Sarahí a few months ago when her 7 -year -old daughter suffered an infection.

“We went to the hospital and the treatments did not serve and every time we were going it was very difficult because, although I have residence permit, they think that one is here and that it is undocumented,” says Alejo, who works in a jarcero and a restaurant.

Then they recommended Hernández. “She gave me the same treatment, but with a big difference, she gave me her phone number, so I could give her every detail of her status, she sent us more exams and we found that she had typhoid.”

And he concludes: “The doctor lifted my daughter, if it hadn't been for her, that bacterium kills her.”

“We see body and soul”

Nezahualcóyotl is a huge municipality attached to Mexico City where almost 2 million people live. It is built, informally, about what was a lake. It has been a destination for decades for those who migrate to the area in search of a job in the capital.

The Busaryry clinic is, 15 years ago, in a two -story house with Viche Green Facade in a residential street in the municipality.

In front, in a pink house, two years ago Sarahí began to see that people with a very different profile were uploaded to the roof than frequents here: Afro -descendants.

With the Frenchman who learned at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he graduated and scored 30 years ago, Hernández established a relationship with a group of 22 Haitians who were on their way to the United States fleeing violence and poverty that whips their country.

“We became friends, the children of the clinic began to play with their children on the street, we gave them food, they did not like the Mexican rice, nor the tortilla, only the breads and the bananas,” says the doctor.

Over time the voice was running that they here provided, sometimes free, sometimes for the usual cost of 200 pesos (about US $ 10), medical services without the need to be part of the official system.

“Brazilians, Venezuelans, Colombians, Cubans began to arrive, all very affected and without money because the migrant route is very hard,” explains Hernández. “There were abuse everywhere and there is still.”

Patch Adams fan, the American doctor who revolutionized medicine with entertaining treatments, Hernández once wanted to be an actress. But, seeing his parents exercise, he understood that humanity that fascinated him of art could translate into medicine.

“I can take you a tumor, but I care more to be able to accompany you in the process,” he says.

Unlike “traditional medicine,” he says, “we see you as the same, without pride.”

“We not only take away the physical pain, but the emotional one; we not only see the body, but also the spirit, the mind and the soul.”

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive a selection of the best content of the week every Friday.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.