-

- Author, Neyaz Farooquee

- Author's title, BBC News, Delhi

-

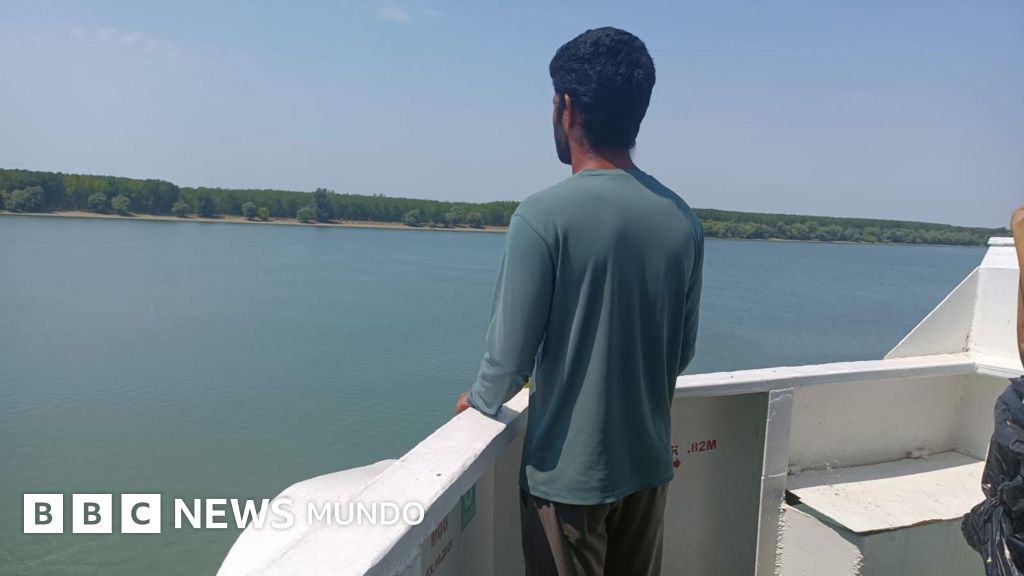

Manas Kumar* has been abandoned in a freighter in Ukrainian waters since April.

The Indian sailor was part of a crew of 14 people who transported corn palomites to Turkey from Moldova when the ship was assaulted on April 18, while navigating the Danube River, which divides Ukraine and Romania.

Ukraine said that the Anka ship was part of the “shadow” roller fleet, used to sell to third Ukrainian grain countries “looted.”

But Kumar, who is the head of Anka officers, said the ship was sailing under the flag of Tanzania and was managed by a Turkish company.

However, in the documents provided by the crew, composed of Kumar, five other Indian citizens, two Azerbaijanos and six Egyptians, it is not clarified to whom the ship belongs to.

Everyone is still on board five months later, despite the fact that the Ukrainian authorities informed them that they could leave because they were not being investigated, according to Kumar.

The problem is that the landing supposes for the crew the loss of their salaries, which in June amounted to US $ 102,828 in total, according to a joint database of abandoned ships maintained by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The BBC has contacted the direction and owners of the ship to know the details provided by the crew.

Kumar states that the crew was unaware of the ship's past at the time of accepting the work. Now, trapped in a situation that escapes its control, the crew wants a quick solution.

He says that the owner and Indian shipping officials continue to ask them for more time to resolve the crisis, but there is still nothing promising.

“This is a war zone. The only thing we want is to go home soon,” he told the BBC.

India is the second world supplier of sailors and crew of commercial ships.

But it also leads the list of crew members known as “abandoned sailors”, a term used by the 2006 maritime work agreement to describe the situation in which shipowners break the ties with the crew and do not provide repatriation, periodic provisions or salaries.

According to the International Federation of Transport Workers (ITF), which represents sea people worldwide, in 2024 there were 3,133 abandoned sailors in 312 ships, of which 899 were of Indian nationality.

For many, abandoning the ship without a salary is not possible, especially if they have already paid strong agents to get the job or to acquire training certifications, explain Mohammad Gulam Ansari, a former sailor who helps repatriate Indian crews from other parts of the world.

According to ITF, the most important reason for abandonment is the widespread practice of registering ships – convenience pavilions – in countries that have little strict navigation standards.

International maritime standards allow a ship to be registered or with a flag in a country other than that of its owners.

“A country can establish a record of ships and collect rates to shipowners, while applying reduced norms in terms of safety and well -being of the crew and, often, does not meet the responsibilities of an authentic state of pavilion,” says the ITF website.

According to the group, this system also hides the identity of the real owner, which helps the dubious owners to cross the ships.

ITF data shows that, in 2024, about 90% of abandoned ships sailed under a convenience flag.

But complications also arise from the globalized nature of the shipping sector, in which owners, managers, pavilions and crews of the ships often come from different countries, according to the observers of the sector.

On January 9, 2025, Captain Amitabh Chaudhary* directed an Iraq freighter to the United Arab Emirates when the bad weather forced him to give a small detour.

Minutes later, the Stratos ship, with a tanzana flag, crashed into some rocks and damaged its tank loaded with oil, forcing an unexpected stop near the Saudi port of Jubail.

The crew – which included nine Indians and an Iraqi – made several attempts to put it afloat, but failed.

Stoned, they waited there for almost six months before the ship was refloated.

For his part, the Iraqi owner of the ship refused to pay them salaries alleging the losses caused by the paralysis of the ship, according to Chaudhary to the BBC.

The BBC contacted the owners of the ship to obtain an answer to these accusations, but did not respond.

Image source, BBC/ITF

The sailors usually blame the maritime regulator of India, the General Directorate (DG) of navigation – objected to verify the credentials of the ships, their owners and the contracting and placement agencies – by the lax scrutiny of the interested parties. The Shipping DG did not respond to a request for comments.

Others, however, point out that even the crew must be more attentive.

“When they hire you, you have enough time to inform the DG Shipping (about any discrepancy in your contract),” says Sushil Deorukhkar, representative of the ITF who works for the welfare of the sailors. “Once you sign the papers, you are trapped and you have to play all the doors to find a solution.”

Things can even be complicated for the crew of Indian property ships that slaughter in the country's waters for various reasons.

Captain Prabjeet Singh worked at Nirvana, an Indian property oil company with Curacao Flag, along with 22 other Indian crew. The ship had recently been sold to a new owner, who wanted to dismantle him, and his salary was in dispute between the new and the former owner.

At the beginning of April, Singh took him to a port of the state of Gujarat, in western India, for his dismantling, when an Indian court ordered his seizure “for default to the crew”, according to the ILO-IMI database.

A few days later, the crew realized that they were abandoned, said Singh. “We were without sufficient food or provisions. The ship had run out of diesel and was in a total blackout,” Singh told the BBC. “We were forced to break and burn the wood of the ship to cook.”

Hired in October 2024, Singh hoped to make a living decently with this work, and that is why leaving the ship without salary was not a viable option for him.

The crew could finally disembark on July 7 after a judicial agreement. But crew salaries are still not paid despite the court order, according to the ILO-IMI database.

Back in the Gulf, Stratos crew said that his greatest fear was that the hole in the bottom of the ship sink him.

But the immediate challenge, they discovered, was hunger.

“For days, we had to eat only rice or potatoes because there were no supplies,” Chaudhary told the BBC last week.

After almost six months, the crew finally managed to refloat the ship, but the accident had damaged the helm, so it was not suitable for navigating.

The crew continues on the ship waiting for the payment of your salaries.

“We continue in the same place and in the same situation. The mind has stopped working, we cannot think what else we should do,” said Chaudhary.

“Can you help us? We just want to go home and meet our loved ones.”

*Some names have been changed to protect the identity of the people consulted for this report.

This article was written and edited by our journalists with the help of an artificial intelligence tool for translation, as part of a pilot program.

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.