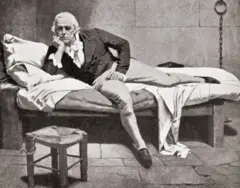

Image source, Getty Images

The secretism that surrounds Masonry feeds all kinds of conspiracy theories.

In the collective imaginary they are accused of moving the threads of power and international finances, of promoting revolutions and handling the rudder of history.

Its hierarchical associative form full of ancient and strict rituals made it prohibited by the Catholic Church, which still considers that its doctrine is irreconcilable with belonging to a Masonic lodge.

Few institutions are more wrapped in mystery and have produced more myths.

One of them is that Freemasonry exerted a fundamental intellectual influence in the French Revolution and the Wars of Independence, carrying liberal ideas and illustration to the emancipation of emerging nations, including the United States and the countries of Latin America.

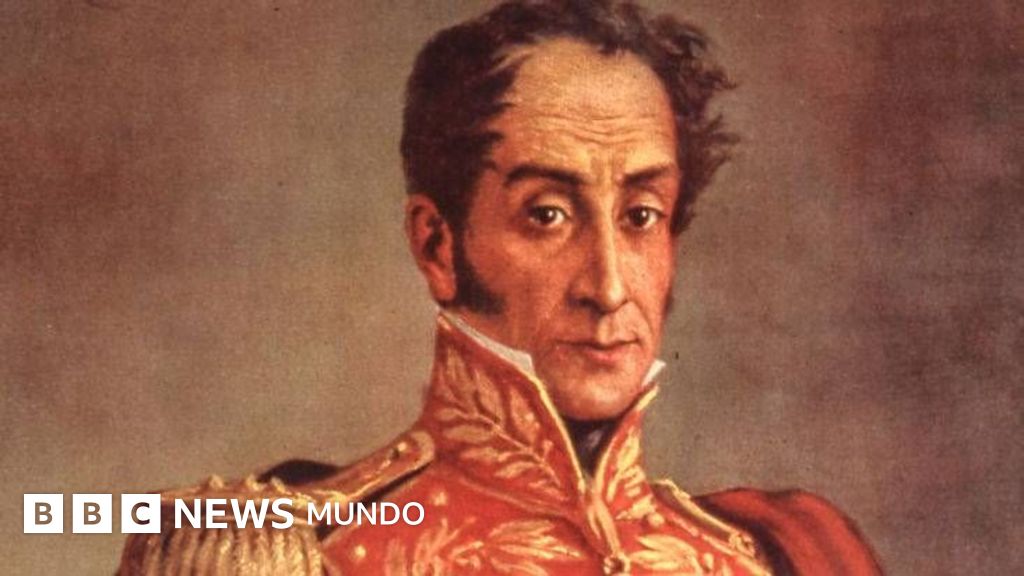

Simón Bolívar, Francisco Miranda, Bernardo O'Higgins, José de San Martín … The legend attributes to Libertadores a Masonic affiliation, and Masonry in general a fundamental role in the processes of independence of Latin American countries.

But how much of legend and how much of reality?

According to Chilean researcher Felipe del Solar, who has thoroughly studied the subject, there were Masons who fought for independence, and the lodges served as a model for the creation of secret societies that allowed Creole elites to group in the colonies and face the crisis of the Spanish crown. But attributing to Masonry the achievement of independence, he values, is “propaganda.”

“In the centenarians of independence, Freemasonry appropriated the heroes and assured that they were all Masons, but it is part of a mythology that Masonry itself created,” the historian explains to BBC world.

Actually, says the academic, “the only documented case of the liberation hero that was Mason is that of Bolívar.” And the documentary evidence also suggests that their participation in Freemasonry was far beyond the initiation rite.

Image source, Getty Images

How Freemasonry came to Latin America

The first Masonic lodges that were founded in Central and South America were established in the Caribbean area in the mid -18th century.

The continent was then part of the different empires that had a presence there, such as Spanish, French, British or Dutch. “At this time it is fundamentally colonial Freemasonry, in which there is an almost null presence of local members. It is an instrument of expansion of the empires,” explains the lot.

Freemasonry had emerged in the European Middle Ages in the quarry guilds. However, it was not until the 18th century that these fraternal associations were established in the modern incarnation that we know today, influenced by the ideas of the illustration of the century of lights and with the aim of looking for meeting places to discuss philosophical, religious and political ideas.

While in the British and French empire, Freemasonry acquired strength and influence and the lodges flourished in its colonies, in the Catholic Spain this institution had been prohibited since 1751 and was persecuted by the Inquisition.

Image source, Getty Images

“In the Hispanic world, Freemasonry was the new heresy of the 18th century, which was assimilated to philosophers and the idea of revolutionary France later,” says Felipe del Solar, who focused his doctoral thesis on this subject.

In those years, according to the researcher, the idea of the “Ghost of Freemasonry” arises, a kind of spectrum that embodies the evil evils despite the fact that the institution was barely a presence in Spain or its colonies.

More than a century later, dictator Francisco Franco continued to blame for an alleged “communist Judeomonic conspiracy” any setback that would affect Spain.

In this way, in the Spanish territories in America, the first lodges that were founded had a very short life.

The first of which there is documentary trail is that of “the three theological virtues”, which was created in Cartagena de Indias, in Colombia, in 1808, but which was quickly discovered.

Its foundation coincides with the invasion of Spain for the Napoleonic troops, when, due to the French influence, different lodges begin to emerge in the Peninsula, which the Creoles lead to America.

About twenty of them are founded in the metropolis, as well as different secret societies such as the Society of Rational Knights in Cádiz, on which experts do not agree on whether it was really a Masonic Lodge or if it was a secret organization that used the formulas and rites of Freemasonry.

“That lodge is returned to America, and founds a similar society in Mexico and another in Buenos Aires, which then is called Louaro Lotia,” explains Felipe del Solar.

The Lautaro Logia

The Lautaro Lodge, which owes its name to a Mapuche leader and had different subsidiaries, including in Santiago de Chile, was a secret society that allowed the opposition to organize with a clearly independence objective. José de San Martín, the general and politician who led the independence of Argentina and Chile, and also Bernardo O'Higgins, known as one of the “parents of the homeland” of Chile.

Image source, Getty Images

According to Chilean-Israelí academic and Mason Leon Zeldis, there is no documentary evidence that neither San Martín nor O'Higgins were Masons, as explained in his essay “the contribution of Freemasonry to South American Independence, an approach based on facts.”

The same libertarian, fraternal and equal spirit that contributed to the development of Masonic lodges and gave them a philanthropic basis “also influenced the leaders of the South American independence movements, without necessarily implying that they were members of Masonic organizations,” he explains.

The objective of the Lautaro Lodge “was not to implement a great republic in Spanish America but several constitutional monarchies with princes of the main European dynasties,” argues the researcher Emilio Ocampo, of the University of Buenos Aires, in an essay on the role of Masonry in the independence process.

As with the Society of Rational Knights, the researchers differ in itself this lodge, which used symbols and rituals borrowed from Freemasonry and had among its members to Masons, was Masonic or not.

For Felipe del Solar, “they were actually secret societies to which Freemasonry had delivered an associative model that was reproduced in different ways in different latitudes.” These groups could have become Masonic lodges themselves, “but it was not a time for Freemasonry to be institutionalized in Latin America because it had a very bad reputation,” according to the historian.

These secret societies become the prelude to political parties in that context of disintegration of the old regime. They serve to join factions that seek to take power and generate reforms.

Image source, Getty Images

Interestingly, they are the anti -demonstration propaganda of the Spanish Empire and the books that are written to denounce the rites and forms of organization of Freemasonry and prevent it from spreading, those who give a model to the Creoles to create the secret societies in which the germ of independence is cooked.

“Independence is not explained by these groups,” says Del Solar, but helps to be irreversible. For example, in the United Provinces of Buenos Aires, what we know today as Argentina, “the Lautaro Lodge was in power at a time of change and led to those changes to be irreversible,” says the expert.

In order for the true Masonic lodges to be institutionalized in Latin America, at least 30 years had to pass, since it was not until the mid -nineteenth century that Freemasonry is founded and becomes an important political power with the arrival of liberal governments in the continent.

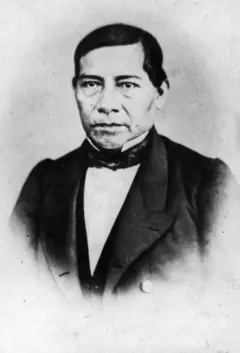

It happens, for example, in Mexico, where several lodges were created after independence, and where there were many presidents.

Mason was, for example, Benito Juárez, “who was the first to elaborate lay laws in an eminently Catholic country, which are a model of lay laws worldwide,” explains Felipe del Solar.

In Cuba, although some early lodges were formed “with a rather colonial and non -revolutionary Freemasonry”, it is not until the end of the 19th century that the institution takes weight and supports the independence of the island.

Bolívar, Mason

Most of the Liberators spent part of their lives in Europe and the United States, where they were impregnated with the philosophical and political ideas of the time.

In many Latin American countries, the idea that much of these independence fighters joined Masonic lodges.

Francisco de Miranda, for example, is attributed to the role of having introduced in Masonry other Latin American patriots in London, where he lived 13 years and where the revolutionary society “great American meeting” created.

Image source, Getty Images

But, according to León Zeldis, “the weight of the evidence shows that Miranda was not a Mason, so the society he founded was not a Masonic lodge.”

According to Felipe del Solar, only two of the Liberators are have documentary evidence: Simón Bolívar and Chilean leader José Miguel Carrera.

Bolívar began in the Lodge of San Alejandro de Scotia in Paris, “on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of the Masonic year of 5805, which corresponds to January 11, 1806,” according to León Zeldis. The document that accredits it is saved in the Lodge Archive of the Supreme Council of Venezuela of Grade 33.

“Bolivar Masonic credentials are unquestionable,” says Zeldis. However, he continues, “it seems that Freemasonry did not play any role in their writings or its activities.”

There are no evidence, for example, that will be affiliated with any of the 30 lodges that existed in Venezuela, Gran Colombia and Ecuador.

Moreover: Bolívar came to ban in 1928 all secret societies, including Freemasonry, when he discovered a plot against him.

So, was Masonry an important influence on his life, his ideas and his actions? The most likely answer, according to the lot, is no.

As for José Miguel Carrera, Saint John started in Lodge number 1 in New York, “where he meets large merchants and arms vendors and thanks to the contacts he generates in these lodges he achieves weapons, two frigates with military and comes to South America to take independence,” explains the Chilean researcher.

Freemasonry opened those doors, but the merchants did not help career because they were a Mason, “but saw in their campaign a good business,” he argues from the lot.

Today it is estimated that there are about 350,000 masons in South America and Central America, with a very relative level of influence for each country.

In Chile, for example, in the 1940s to 1960s, four of the five presidents that the country had were Masons, as well as more than half of the Parliament, judges or police, recalls Felipe del Solar. “It was an impressive power.”

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.