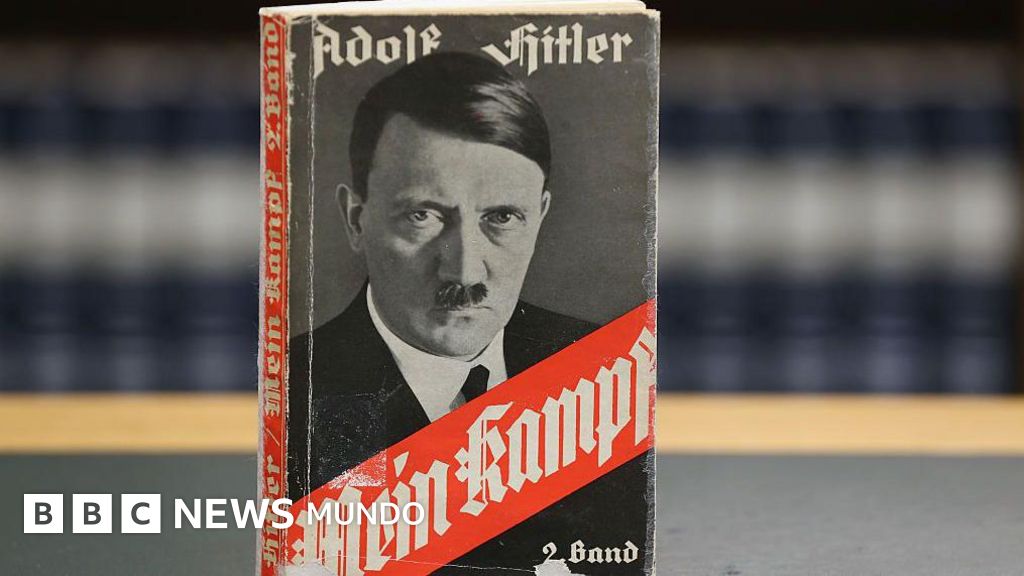

Image source, Getty Images

-

- Author, John Murphy *

- Author's title, BBC

Every time I tell someone that my Irish grandfather translated “Mein Kampf” (“My fight”) by Adolfo Hitler, the first reaction is usually to ask me why. The following is the inevitable: “Was it Nazi?”

I simply answer: “No, I wasn't Nazi” (the explanation below) and “why wasn't I going to translate it?”

My grandfather was a journalist and translator who lived in Berlin in the 30s and so it was how he earned a living.

Wasn't it important for Europeans to understand what the “great dictator” was (apologies to Charlie Chaplin)?

Surely my grandfather and many others who were not Nazis thought that undoubtedly yes at that time. And let's not forget that he did it before Hitler became the most notorious incarnation of evil.

Hitler made a fortune with his book, which he wrote in 1924, and in which he exposes his ideas about German nationalism, anti -Semitism and racism.

Not only did he exempt paying taxes on the text but after he became a German chancellor bought millions of copies to give them to newly married.

It is estimated that only 12 million copies were sold in Germany.

Intrigue history

The history of my grandfather's translation – the first full version in English, which was eventually published in London in 1939 – is an intrigue that involves concerns by copyright, a discreet trip back to Nazi Germany and a Soviet spy.

My grandfather, James Murphy, lived in Berlin since 1929 before the Nazis came to power. He founded a magazine for intellectuals called “The International Forum” whose content was mainly translations of interviews with eminent characters, such as Albert Einstein or Thomas Mann.

However, the bad situation of the economy forced him to return to the United Kingdom.

Image source, Gentileza John Murphy

While there was my grandfather wrote a small book entitled “Adolf Hitler: the drama of his career”, which tried to explain why so many Germans were attracted to the Nazi cause.

Then he returned to Berlin, in 1934, where he considered ridiculous the distorted translations of the statements of Nazi politicians.

He was especially critical of a reduced version of “My fight”, just one third of the size of the two volumes of the original published in English in 1933.

By the end of 1936 the Nazis asked him to work in a translation of the full version. It is not clear why. Maybe the propaganda minister wanted an English version when he considered it convenient.

But at one point in 1937 the Nazis changed their minds. The Ministry seized all the complete copies of Murphy's manuscript.

He returned to England in September 1938 where he soon found editors excited about the idea of printing his translation, although concerned with copyright. Anyway, Murphy had left his complete job in Germany.

Just when I was about to travel back to Berlin to fix the problem, he received a message from the German embassy in London telling him that he was not welcome.

The news devastated it; He was a natural wasteful and had run out of money. He had his hopes put in the publication of Hitler's book in English. It was then that his wife, my grandmother, offered to go in her place.

“They will not know who I am,” said my father, Patrick Murphy. “So it was my grandmother who returned to Germany where she cited with a Nazi official she knew in the Propaganda Ministry, a man named Seyferth,” says my father.

Image source, Gentileza John Murphy

In Berlin

Unfortunately, Mary Murphy had chosen a bad day, on November 10, 1938, the morning after the “Broken Crystals”, when Jewish stores were attacked by Nazis bands. However, the appointment was not canceled.

“There is a group of Americans working in a translation right now, so they will not be able to prevent him from leaving,” said the Nazi official.

“You know that my husband made a precise and fair translation, an excellent translation, why don't they give us the manuscript?”

Seyferth refused. “I have a wife and two children. Do you want me to end on the wall and shoot me?”

Then Mary remembered that her husband had given one of the first drafts to one of her secretaries, an English woman named Daphne French.

He looked for her in Berlin and, luckily, she still had the copy. Mary took her to London. With the American translation about to leave, there was a career for my grandfather's to be published as soon as possible.

In March 1939, Hurts and Blacktt/Hutchinson published the first British version without purging “my fight.”

Image source, Gentileza John Murphy

In August of that year, 32,000 copies had been sold and the book continued to print until the day when a German bombardment destroyed the printing press.

The new US version became the standard. An copyright expert who has written about “my fight” estimates that Murphy's edition sold between 150,000 and 200,000 copies.

My grandfather, however, did not receive royalties. Hutchinson argued that the German government had already paid him and that copyright had not yet been insured, so they could be sued by the Nazi Eher Verlag publishing house.

And an official letter from Germany, which was rather a diatribe against James Murphy, made it clear that Berlin did not approve his translation.

But the Germans did nothing. Eher Verlag even requested copies of courtesy and the payment of royalties. They never received anything.

Murphy's edition is discontinued and although you can find copies scattered around the world, it is also available online.

Authoro by the author

In the Wiener Library safe in London, which has an extensive collection of holocaust and genocide material, there is a copy of the Murphy translation.

In the guardian of the book there is a photograph of Hitler and a group of smiling people in Berchtesgarden, in the Alpes Bávaros.

A pencil written note explains that Hitler arrived in the town to sign copies of “my fight.” And there is your signature, in pencil.

The book, bought in 1939 in the United Kingdom, was apparently of British fans who visited Hitler in his alpine retreat.

The photograph has some annotations, with three arrows: in one you read “M. Bumann?”, Simply “Hitler” in the other and finally the last one that points to a young woman dressed in white who says “Karen”.

Image source, AFP

“It's always a bit chilling to hold the book in hand, knowing that he had it in his hands when he signed it,” says Ben Barkow, library director.

Then it shows us an edition of the Murphy translation that was sold in 18 weekly separatas.

The extraordinary, however, is what he says under the roof: “Royalties of all sales will go to the British Red Cross.”

On the other side he says: “Route map of German imperialism. The most discussed book in the modern world.”

Spies

There is another intriguing turn in the history of translation. While my grandfather worked in the book, he hired the help of a German who had recommended a Jewish writer who was also his homemade.

James referred to Greta Lorcke – as he called then – as one of the smartest people he had met.

But he had several fights with her. While he wanted to produce a translation the most readable, in good English, Greta sometimes changed it to reflect the convoluted and vulgar language of Hilter.

“That bothered my grandfather,” says my father. “And I changed it again.”

Image source, Gentileza John Murphy

But there was something else about Greta that my grandfather did not know. During the war, the Nazis discovered that Greta and her husband, Adam Kuckhoff, was the well -known circle of Soviet spies “the red orchestra”.

Kuckhoff was executed while Greta was commuted to the sentence by life imprisonment. He survived the war and in his autobiography he describes his first encounter with Murphy.

“He left me very impressed when he came to meet me in the main lobby. He was handsome, two meters away and with 100 kilos of aristocratic dignity, a man who inspired confidence. The way we discussed his translation, with whom he was going to help him, made me believe that he was not a sympathizer of National Socialism,” he wrote.

Greta had many doubts about whether she should translate “my fight”, as explained to my father years later.

“'Why would this man help translate into this terrible book into English?'

“They knew it for the Soviet ambassador to London, Maisky, who knew the (former British premier David) Lloyd George very well. Lloyd George had told Maisky 'I don't know why you tell me that all that is in ´Mi struggles.' I read it and it is not.”

It turns out that George had read a reduced and controlled version by the Nazis. Some of the worst things had taken them out. That had told Greta. “They must help this man, translate it.”

It's a pity, but I didn't meet my grandfather. He died from heart problems in 1946, just before turning 66.

He was a man as complicated as fascinating.

He was a true scholar, knowledgeable about literature, art and science, a journalist, professor, translator and expert in Italian fascism and German Nazism.

He spoke French, Italian and German. I dreamed with some United States in peace.

However, in the end, although it was not his intention, he will be remembered more for being the man who translated “my fight.”

* This note was originally posted in January 2015

Subscribe here To our new newsletter to receive every Friday a selection of our best content of the week.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.